Saturday last I was fortunate enough to attend a day of lectures by one of our officers, who I will just call Major Jim, on tactics in the attack and defence. This lecture was for a mixed audience of ranks and units, Regular and Reserve, conducted at the armouries of the South Alberta Light Horse (affectionately called the Sally Horse) Squadron in Medicine Hat, AB.

As an aside to military historians out there, the SALH served in the Normandy Campaign as the South Alberta Horse, and one of their officers, Major D.V. Currie, a welder from Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan before the war, is the only officer of the Royal Canadian Armoured Corps to have won the Victoria Cross for his actions near Falaise in Normandy. That's Currie, below left, holding the revolver, in this famous photograph.

Here is Major Jim, holding forth on the armoury floor, in a photo I sent to him entitled "Master of the Battlefield". Jim wrote back to say "Apparently either I went to mime school, or I was getting ready to meet a female later that day." Jim came up from the ranks, served on nine (maybe more that he can't talk about) deployments, was shot while in Bosnia (his advice, "Don't get shot, it's really painful and it sucks"), and instructed at the infantry training centre at CFB Wainwright. He knows his stuff, and despite his claims that he is merely a dumb infanteer, is easily one of the smartest and nicest guys I've met in the Army, though he could probably kill me three different ways with a coffee stir stick.

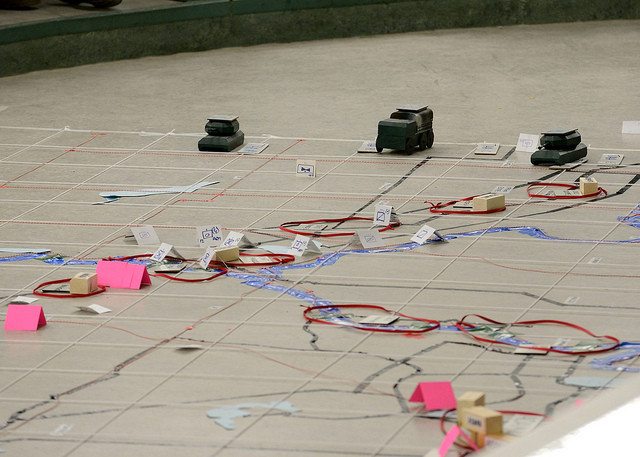

The rather unconvincing map, made of a large tarp and three dozen boxes of printer paper, illustrated a ridge line, and the problems discussed were how to attack and defend this ridge using a combined arms force that looked like the Canadian Army plus kit (ATGMs, attack helicopters, mortars and even MLRS systems) that we no longer have or have never had in our order of battle. The OPFOR (opposing force) was a combined arms force using Russian kit (BRDMs, BMPs, T55s and better). When I asked Jim latter why we were still talking about fighting the Warsaw Pact, his answer was that Army doctrine is now shifting back to basics, on the theory that we are at risk of losing key knowledge following ten years of fighting a lightly armed insurgency in Afghanistan. When one considers that our next deployments may be to African hotspots where the bad guys do have armour and aviation, this shift makes sense.

Speaking of gaps in the Canadian Army inventory, I have to say that there was a shocking lack of toys, and what we did have to work with was in pretty rough shape. Unacceptable! Damn these budget cuts and these parsiminous pennypinching parliamentarians!

I have to confess that I spent the day using my wargaming ears more than my chaplain ears, though it was interesting to think of how my trade might be employed in a more mobile, conventional war. In Afghanistan chaplains are mostly confined to bases, but in a force on force war we should go back to our traditional places forward, such as Casualty Collection Stations, but that's another point. As a wargamer there were two things that really stood out for me.

The first was Major Jim's emphasis on recconaissance in the attack, which may have been tailored to his audience since the SALH now have an armoured recce role. To the question, what should recce elements be looking for and noting, his answer, repeatedly, was EVERYTHING. Everything seen on recce is of potential use to the commander planning his attack, from the location of kill zones, of run-ups and gaps in the obstacles on a defensive position (showing the likely moves of the armoured counterforce) to plumes of exhaust seen during engine warm up cycles (how many vehicles are present, in what shape are they, how good is the enemy's training, etc). I got to thinking of how badly recce elements are often represented in wargaming, on the level of, here are your armoured cars, go get them killed and find out what's under those blinds. I would love to see a scneario where the goal was to approach an enemy position, develop as complete picture of it, and safely get back to report. I'm not sure how much fun that would be for two players, but it might work well solitaire or as a team game with a referee playing the enemy.

The second learning for me was the importance of the mobile defense. As Jim explained it, defending the position alone is a good way to lose, as the enemy have the freedom to maneuvre into attack positions without hindrance, can get get good locations for FOOs and FACs, and can coordinate their attacks with artillery designed to suppress and disrupt rear areas, resupply points, and routes for the enemy countermove force. If however the defender has sufficient forces to put a guard force ahead of his main defensive position (MDP), he can trade ground for time, and strip away enemy resources (first recce, then anti-tank, then command and control, etc), this forcing the enemy to attack blind and uncoordinated, or to delay the attack while fresh forces are brought up. Modern wargamers schooled in NATO vs Pact will understand this theory better than I do. In most games I've seen and played in, the constraint of available table space forces one to play a set-piece battle, where the fight happens on or very close to the main defensive position. It would be interesting to have the time to play the defensive battle in several phases, first the battle of the guard, second the withdrawal of the guard through the MDP, and third the fight for the MDP itself. In each successive phase, losses would be deducted and capabilities removed from both side depending on how they fared in the previous phase. This could be more easily done in smaller scales than in big ones, I think.

I could go on, but I think you get the point that it was an interesting day, with much to absorb, and with much food for thought for the wargamer. It leads me to wonder, for those of you who are trained in military operations and tactics, how much of your training to you get to use on the wargames table?