One of the pleasures of having access to a university library is the new book shelf. God knows I have enough to read, but I can’t resist checking out the new books from time to time. Often I learn about books I would never otherwise have heard of.

Boris Sokolov is a Russian author based in Moscow. He held an academic post at the Russian State Social University until 2008, when he claims he was dismissed for writing an article critical of Russia’s war with Georgia that year. Other than that, I don’t know anything about him or his qualifications, but he seems to have written a lot.

The Role of the Soviet Union in the Second World War, translated and edited by Stuart Britton (Helion and Company, 2013, ISBN 978-1-908916-55-6), is a set of essays that are sometimes dense and packed with statistics, but which make several points that I didn’t know about. Wargamers with an interest in the Eastern Front in World War Two might be interested in the four things I learned from this book.

1) Hitler beat Stalin to the punch. Sokolov is one of several Russian scholars who believe Stalin was planning a pre-emptive strike against Germany. As early as May 15 1941 Red Army planners were preparing to “forestall the enemy in deploying and attack the Germany Army when it is in a state of deployment but has not yet been able to organize the front” (21). At this time Stalin was worried about a possible British collapse, freeing all German forces for an offensive, so in the second half of May called up 800,000 reservists, transferred large formations to the Western Districts, and was even forming a Polish division for operations in German-occupied Poland. The idea was that by June the Red Army could mass forces between 20-80 kilometres from the border, deploying aviation to forward airfields, in preparation for an attack most likely on Sunday, 6 July. These plans ignored the fact that the Soviet military was not ready for war. There was not enough fuel for air and ground operations, and tank and air crews had only a fraction of the training time they needed. There is a fascinating “what-if” scenario here, if the Soviets would have landed the first punch and not been forestalled by Barbarossa in June. I rather doubt it would have gone well for them, and might even have been a worse result than what actually happened.

2) Kursk was far more costly than the Soviets admitted. While still a victory for them, the Soviets exaggerated German casualties “several times over” while concealing their own “disastrous” losses. The numbers in this chapter are quite confusing, but I gather from Sokolov’s argument that the Red Army lost 1,677,000 killed, wounded and captured in the whole battle, whereas Wehrmacht casualties were most likely 360,000, a ration of 4 to 1. Soviet tank losses were a little over 6,000, about 4 times the figure for German tank losses (1,500) in traditional Soviet accounts, another 4-1 ration. “This very unfavourable ration of losses may be explained by the superiority of the new Gemran tanks and also the superiority of German command and control in armour combat. … Another cause was the comparatively low level of training of Soviet personnel, especially of tank-driver mechanics, who until the end of 1942 received only from 5-10 hours of driving practice, when the necessary minimum was 25 hours (43)."

3) Lend Lease saved the USSR. An official Soviet history of the Great Patriotic War states that assistance from the Allies “was in no way meaningful and could have had no decisive influence on the course of the GPW” (48), when in fact in 1963 Zhukov himself was heard to admit that without this aid “we could not have formed our reserves and could not have continued the war” (49). Lend-Lease aid included everything from fuel to steel and aluminium to railroad equipment and explosives for making munitions. Just one of many statistics in this chapter. From July 41 to Dec 43 the Soviets made 30,000 T-34 tanks, each of which required 20 tons of armoured steel, far more than the USSR could produce. If Sokolov is right, almost half of those T34s were made with Lend-Lease armour.

4) World War Two was a massive human catastrophe for the USSR. Hard data on Soviet military losses is very hard to come by, and trustworthy research was not started unit the late 1980s. In reviewing this research, Sokolov puts total Soviet dead at almost 43.5 million, compared to just under 6 million Germans. These figures include military and civilian deaths, as well as potential losses from falling birth rates, which may seem to some as an exaggeration. Even removing the unborn from the equation, the totals are sobering: 26,548,000 Soviet military dead vs 3,950,000 German military dead, and 16,900,000 Soviet civilians dead vs 2,000,000 German civilians dead These figures are approximations. Very few casualty estimates were published in the Soviet era and exact figures are hard to come by because for the first year of the war, many Soviet soldiers were not given identity cards, service or pay books, just (if they were lucky) uniforms and weapons (67). These high casualties and the massive turnover of personnel in Soviet units as losses were replaced by meant that right up until the end of the war, those who were newly mobilized entered battle poorly trained in military matters” (75), and thus “The Red Army had to pay in blood for industrial backwardness and the inability to use combat equipment intelligently” (91), compounded by the Soviet leadership’s indifference to casualties.

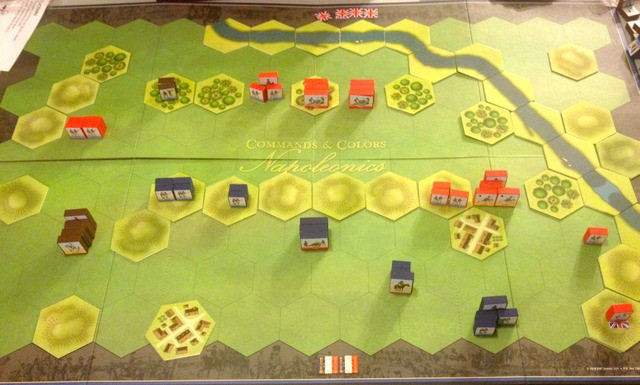

Some thoughts for war gamers.

The Ostfront is always a compelling subject for war gamers, and yet it is one of the bleakest and most tragic spectacles of military history. This book just makes it all the sadder. I have to take Sokolov’s figures with a grain of salt, since I haven’t seen any scholarly reviews of this book in academic literature and for all I know the man is a bit of a flake. However, assuming he is near the truth, what does this mean for war gamers? I would say that any rules set which doesn’t handicap the Soviets in leadership and tactics doesn’t reflect history. I know this has long been a debate in wargaming as to whether the Germans are too often portrayed as supermen, and I think those questions are fair. Certainly by 1943 on the Wehrmacht was being ground down and losing its edge, but I think in almost every case until the end of the war the Germans should have an edge in training, tactics and leadership, a qualitative superiority vs the Soviet quantitative superiority.

I got to thinking as I read this book, will we see more of this kind of scholarship coming from Putin-era Russia? A lot of the evidence and scholarship Sokolov cites comes from the late 1980s on, the era of glasnost and post-Soviet opening up of the archives. It worries me that if Russia goes further down the path of nationalism and chauvinism, we will see a new clampdown on scholars who want to mine the archives for a story that still hasn’t been properly told.