On Twitter today, Nick (@Dozibugger)of the Too Fat Lardies crew flagged this short piece on a British Army professional development website by Dermot Rooney.

The gist of the article is that the pendulum in debates about infantry doctrine swings between Attrition and Manoeuvre. Attrition is relatively easy to model in simulations because it can be matched to the known lethality effects of weapons systems (eg blast radius) whereas manoeuvre is harder to model because it depends on psychological factors (surrendering when you know you are outflanked and beaten). In other words, you can defeat the enemy at the tactical level through Attrition, as summarized in the saying “close with and destroy”, or by “manoeuvre and cleverness”.

Attrition can seem more understandable because you can use numbers and models to analyze and predict the expected results of weapons systems, whereas Manoeuvre is a subtle art and hard to quantify. Also, Attrition may seem more attractive to planners and accountants because the cost of a weapons system can be justified by its predicted effectiveness, whereas Manoeuvre is an expensive proposition that requires extensive combined arms training in the field, and its expected results are hard to model, because at its core Manoeuvre is about psychology:

“Manoeuvrism hinges on two psychological tricks: 1. Give the enemy more things to think about than he can handle; 2. Make it obvious that he’s going to lose."

Rooney notes that Manoeuvre on the battlefield is typically a low-level activity. At the operational level, there may not be advantages of terrain or surprise that allow a general and his staff to be very clever. Rooney quotes the British general Horrocks, who said of Operation Veritable (1945) that “There was no room for manoeuvre and no scope for cleverness”, but once the operation was under way, there were opportunities for his tactical leaders to get into positions where they could persuade enemy soldiers that they were beaten.

Surely this is true of the wargames table. It seems to me that the more units we put on the table, the more we move the pendulum towards Attrition. I am thinking of an AAR I saw recently for a Team Yankee game, where the table was packed with models and there was little opportunity for the attacker to do anything but trust in firepower to plow through. Likewise the big battles so beloved of us gamers, whether Waterloo or a 2500 point per side W40K game, surely are resolved by Attrition.

In such games, a player will not be willing to concede defeat until the math works remorselessly in the opponent’s favour. We can model psychology in rules such as “Army Break Points” but those rules are only triggered by a sufficient amount of Attrition.

So what would a game look like if it was set up more at the Manoeuvre end of the pendulum? It would presumably have fewer units, and a table that allowed more movement and less sheer brute force frontal battering. It would also model the effects of combined fires, including the loss of initiative, command and control, and morale under the effects of those fires.

Of course, there are all sorts of mechanisms out there already which try to include these factors, including rules for troop quality types, the cumulative effects of shock, and the gradual loss of command and control as leaders are lost. None of this is new. Rules systems like WRG have modelled the effects of being flanked on morale checks forever.

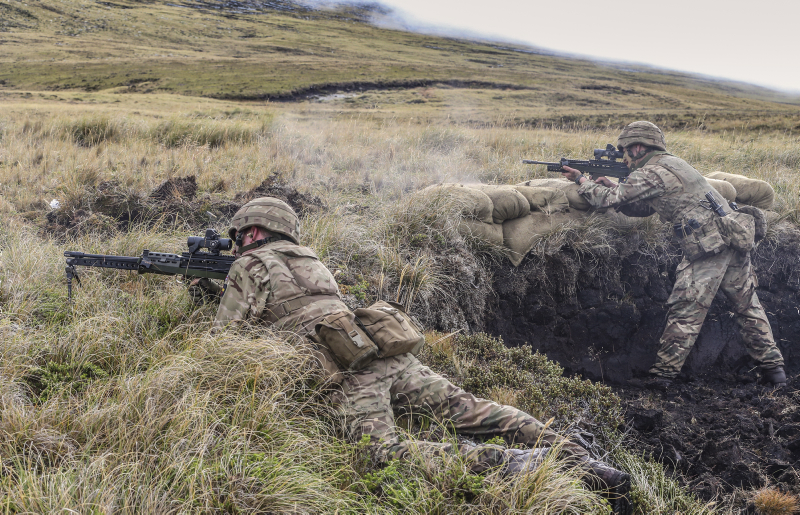

In his article, Rooney says that “Sometimes there’s a cellar of scared men waiting to put their hands up; sometimes there’s a fight right up until the last few metres and then a Mexican wave of surrendering happens”. I guess that’s really the challenge for tactical wargamers - at what point does that seemingly impregnable unit, dug in with hard cover, suddenly become those scared men waiting to put their hands up? And, more mysteriously, at what point does my opponent across the table start to lose heart as the battle turns against him/her?

Surrendered British paras at Anhem. What makes the best troops decide that they’re done?

I don’t have all the answers to this, but for years now I have used this quote at the end of my work email signature block, from B.H. Liddell Hart: “Loss of hope, rather than loss of life, is the factor that really decides was, battles, and even the smallest combats”.

Blessings to your die rolls.

MP+

An interesting yopic, Michael. That quotation defining 'manoeuvre', though, in my view might equally apply to attrition. How? Years ago - speaking as a non-military war gamer, you understand - I gave as my method of attack as 'presenting the defenders with roo many targets to shoot, and trusting that the scale and ferocity of the assault of the assault would induce a sense of inexorability - it just could not be stopped'.

ReplyDeleteThe large scale late battles of Napoleon yurned rather into battles of attrition, I think, and maybe even in 'real life' increased scale tends towards attrition. At Borodino, Davout sought to manoeuvre the Grande Armee into a more favourable position before attacking. napoleon's refusal to do so (possibly fearing that the attempt would merely manoeuvre the Russians out of their position, deferring once again the decisive battle napoleon sought.

The Western and Eastern fronts were bereft of manoeuvre until lessons learned at the minor tactical level offered at some flweting chances of infiltration, bypassing strength and attacking weakness. I think that is why I (among many) find that conflict unappealing: it is difficult to carry out such manoeuvres on the table top.

I have occasionally noriced, though , the manner in which an apparent deadlock can be resolved suddenly, with the collapse of one side. I am reminded of the comment made to General P.G.T. Beauregard at Dhiloh, in which, after nearly ewo days of battle, the Confederate Army was likened to a sugar cube soaked in water: still holding its shape, but in imminent danger of collapsing and dissolving.

I recall a refight of the Battle of Castalla (Spain, 1813) with a friend, many years ago. I had the French. My guys managed after much effort to clear the ridges. Reaching the eastern end, they looked down into the town itself, packed with British and Spanish troops. My guys had pretty much spent their whole strength levering the Allies off the ridge. So I called the retreat.

Never would I have believed the speed and ferocity of the Allied counter-offensive. As my troops reeled back towards the Pass of Biar, they were only barely fending off the enemy attacks, broken units were given no chance to rally, and things got even stickier once they reached the defile. This from an army that I had driven, with hard fighting, from the ridge tops.

Though I lost that battle (and the same action a few years later in exactly the same way), I have always regarded it as one of the most engaging and fun war games battles I've ever fought/played.

An interesting post and one which much to ponder upon. I think you are indeed on to something with what you say. I really like your emiail quote. Perhaps it is only me but l miss the morale tests of my wrg 6th edition days. I enjoy Dbm but miss that dice throw and recalling the factors from memory. It did not take ages nor was it interrupting the game . One got to the stage of only having to throw throw dice to be aware whether or not it was necessary to total up factors. To me it replicates nicely the combination of a chance factor in morale as well as taking into account battlefield circumstances.

ReplyDeleteI find that I enjoy games with objectives and of manover over games of attrition. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteDefinitely not a fan of attrition long been a fan of trying to use the various principles of war in wargames (surprise, concentration of effort, etc) but on a game table where you know your opponent(s) psychology can also come into play. Hmm he usually does this and I usually do this so if I make it look like I'm doing this but do that instead......of course if your opponent knows you well he may notice and see through you so best stick to sound principles while being sneaky but there have been some memorable gotcha! moments.

ReplyDeleteOn the other hand, I can recall a game where we were ahead and the player elected to overall command despaired and surrendered at some minor setback... WHAT????

I followed that tweet yesterday too. Most fascinating. Gives pause for thought, and like everyone else, I'm not sure I have any answers of the how, other than it occurs when opportunity presents itself.

ReplyDeleteGreat post, very interesting.

ReplyDelete